Mastering basic strategy at blackjack means more than memorizing a chart. It’s about understanding how to play offense and defense.

By playing offense—making the extra bet and splitting the 8s—we create a situation where we have an edge. Each of our 8s is a stronger building block than the dealer’s 6.

The Theory of Blackjack by Peter Griffin This is the classic blackjack book on the mathematics of the game and includes a complete discussion of basic strategy and card counting systems including single and multi-parameter. Newer editions come with a complete index. Editor note: Peter Griffin died from cancer at the age of 61 on Oct. Ken Uston’s book Million Dollar Blackjack is the third book in the quartet of required reading. Ken Uston even after his death remains one of the most controversial players in the history of the game. MDB is an amazing book and Uston’s breakdown of complex ideas to simple and understandable form remains his greatest achievement.

My friend Ralph has been playing blackjack for decades, even longer than myself. He’d never really studied the game, but absorbed enough through all that play that he was an OK basic strategy player—as long as we were talking only about hard totals. If he had a hard 16, he was always going to hit if the dealer had a 7 or higher, and stand if a dealer had a 6 or lower. With those types of hard total plays, he usually made the right call.

But when it came to pair splitting, or soft totals, his strategies got fuzzy. He had his own ideas on when to double down on a soft 16, or when to split a pair of 9s, that weren’t always in accordance with basic strategy. Truth be told, they weren’t always in accordance with his strategy the last time he played. He made these decisions based on his instincts and hunches.

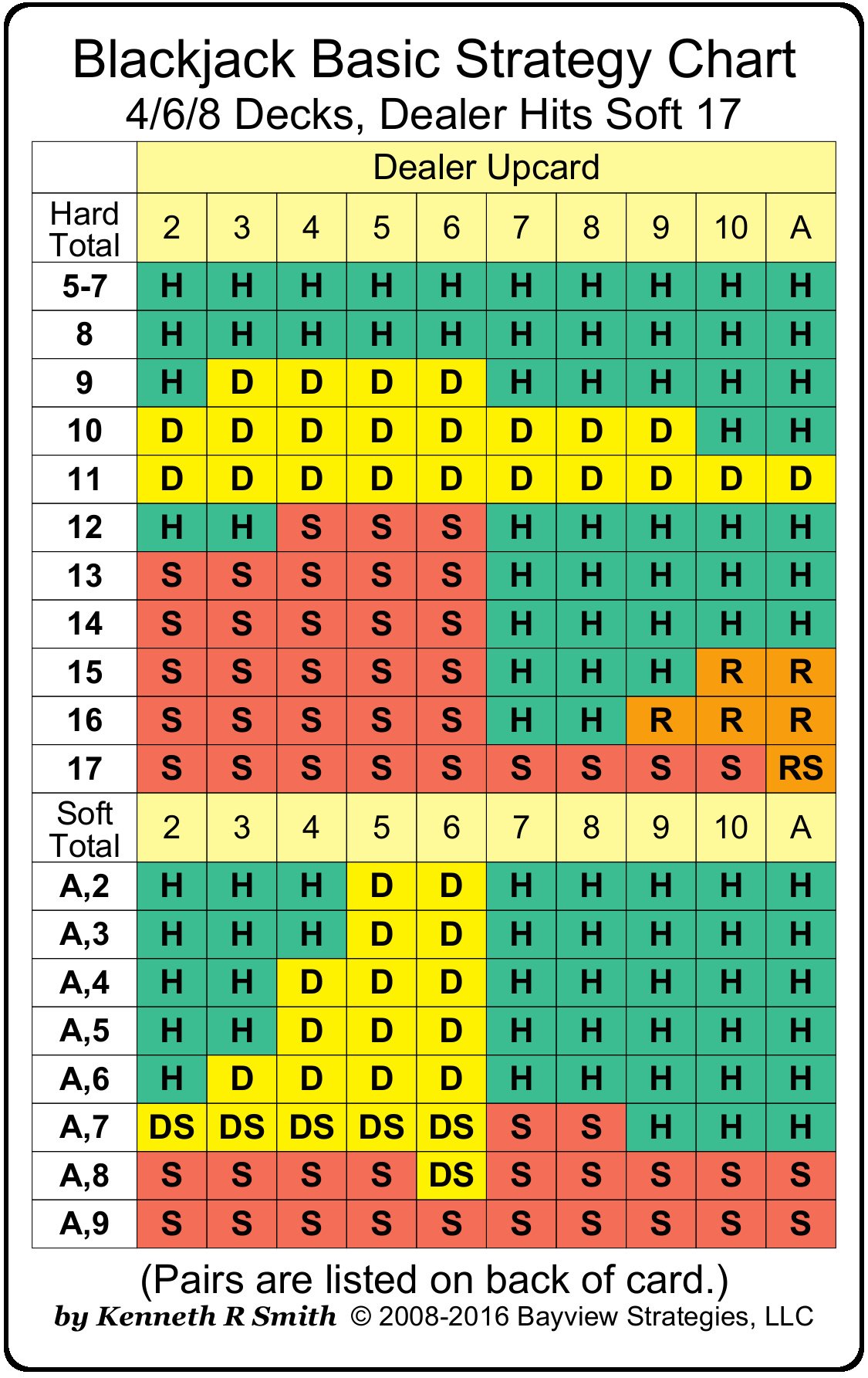

One night, while we were out at dinner, he took a piece of paper from his shirt pocket and unfolded it. Ourwives rolled their eyes. It was a basic strategy chart.

“I’ve decided to do this right,” he said. “Should have done it years ago. I bought a book on blackjack, and some software to practice on, and I’m trying to do everything they tell me. But I’m having a few problems…”

What followed was a lengthy question-and-answer session between Ralph and myself, in which he challenged me on many of the finer points of blackjack play. I’d like to share Ralph’s questions, and my replies, with you. I think this conversation illustrated a number of common questions that players have about basic strategy, which may not always feel like the right way to play—but I can assure you, it’s the mathematically correct way to play.

Sticking with basic strategy, even when your “gut” is telling you otherwise, gives you the best possible chance of winning more and losing less. It also helps to understand why certain plays are correct. While basic strategy isn’t difficult to memorize, it’s often easier to stick to when you understand the underlying concepts of why you’re splitting or doubling down in a particular situation.

The way I like to explain it, certain plays are offensive (meant to capitalize on the dealer’s vulnerability), while others are defensive (designed to minimize your losses when the odds are clearly against you).

Anyway, the first “problem” Ralph had with his study materials was this: “The book says to split 8s no matter what a dealer has face up. I’ve never split 8s when the dealer has a 10 or a face, but the book and the software say the same thing; you’re supposed to do it. What do you think?”

I told him I thought the best play is to split 8s, no matter what the dealer has.

“But why?” he protested. “Even if I get 10s on both 8s, which gives me two 18s, those are just two losing hands if the dealer has a 10 down for a 20.”

Well, yes, that does happen sometimes.

“And still you tell me to split?”

Sometimes blackjack is about playing offense, and sometimes it’s about playing defense. When you have 8s against a 10, it’s time for a little defense.

“Well, making an extra bet in a losing situation seems pretty offensive to me. But go ahead. Tell me about offense and defense.”

Going on the offense in blackjack means pressing an advantage. Double down situations are an example. In a common six-deck game where the dealer stands on all 17s, we expect to win more often than we lose if our first two cards total 11 and the dealer is showing anywhere from a 2 through a 10-value card. We have the advantage, and we double down to maximize profit potential.

“I get that. But isn’t it the same when we’re splitting pairs? Don’t you bet more money to make bigger profits?”

Not always. Sometimes we split pairs to turn a losing situation into a winner. We started off here talking about pairs of 8s. Well, when we split 8s against a dealer’s 6. That’s just what we’re doing. We’re taking a hand that’s a loser if we play it as a 16 and turn it into a money-maker.

“So we’re playing offense there, right? But why does the dealer have an edge with a 6?”

Because 16 is such a terrible hand for players. If we don’t split the pair, we have two options. We can stand, and hope the dealer busts. But the dealer busts when showing a 6 only about 42 percent of the time. The other 58 percent of the time, the dealer makes a 17 or better and beats our 16.

If we play the pair of 8s as a 16 and hit, then we bust a little less than 62 percent of the time. We lose even more often than we would by standing on the 16.

By playing offense—making the extra bet and splitting the 8s—we create a situation where we have an edge. Each of our 8s is a stronger building block than the dealer’s 6.

“OK, but so far you’ve been talking about offense. What about defense? Why should I split my 8s when the dealer has a 10?”

Because you’ll lose less money that way. When we play offense, it’s because we want to win more. When we play defense, it’s because we’re caught in a tough situation and want to lose less.

“I’d rather try to win, thanks.”

So would I. Unfortunately, there are times in blackjack when we’re dealt a losing hand, and it’s up to us to make the best of it. A pair of 8s against a dealer’s 10 is one of those times. If we play it as 16 and hit, we’re going to bust a little under 62 percent of the time. If we stand, we’re going to lose the 77 percent of the time that the dealer makes 17 or better.

Blackjack Book Odds

“Just like any other 16 against a 10. Rock and a hard place.”

Right. But when that 16 is a pair of 8s, we have an option. We can make a second bet, and split the pair, and start two hands with 8 against 10. That’s not a great position. The dealer still has an advantage. But it’s a far sight better than 16 against 10.

“How much better?”

If you hit, as we would on other hard 16s, your expected losses are about $54 per $100 wagered. If you split, the expected losses drop to $49 per $100 in initial wagers. Even though you’re doubling your wagers and now really betting $200 instead of $100, your average losses drop to $49. By playing defense, you save yourself a little money.

“But just last week I tried it out, split the 8s and got a 10 on each one. I didn’t feel too bad about having two 18s, but then the dealer turned up another 10 for a 20, and took all my money. Isn’t that the most likely outcome?”

When you split 8s, the dealer will have a 10 value face down about a third of the time. We can throw Aces out of the calculation. If the dealer has an Ace down to go with his 10 up, that’s a blackjack that stops play before you’d have an chance to split the pair. Of the other 12 card denominations, four are 10 values — 10s, Jacks, Queens, Kings and Aces. So the dealer will have a 10 value down about a third of the time.

That still leaves two-thirds of the time when you’re splitting 8s against a dealer’s 10 that the dealer does not have a 10 face down. And the precise situation you described — player gets 10s on top of each split 8 and the dealer has a 10 down — occurs only one-third times one-third times one-third, or once per 27 hands when we split 8s against a 10.

“So you’re telling me I should split the 8s, even though sometimes I’ll lose two hands instead of just one?”

Yep. Not all blackjack plays can make money for you, but it’s worth playing a little defense sometimes. Losing less is a better deal than losing more.